This winter, Netflix officially removed Moana from its catalog of streaming movies, a devastating blow to my house with two pre-schoolers. It had easily been the most played show on our account for the better part of 2018.

My kids love Moana, and I have to admit, I’ve enjoyed it too. Thankfully my kids are young enough to have missed out on the Frozen craze. I’d take listening to Moana over Elisa any day. The music and incredible visuals make Moana a movie hard not to like and hard not to get stuck in your head.

The Hero’s Journey

Upon Moana’s release in 2016, The Verge wrote: “after 80 years of experiments, Disney has made the perfect Disney movie.” Families seem to have come to a similar conclusion. My four-year-old son has even managed to request the movie’s soundtrack by asking our Amazon Echo to play “the crab song” or “the Maui song.” Enough kids must be putting in the request for Alexa’s algorithm to have learned that “the crab song” is actually “Shiny by Jemaine Clement.” That song has almost 200 million views on youtube, coming in behind “How Far I’ll Go” with 395 million, and that’s not counting the unofficial bootleg copies.

Watching Moana for the first time, I was struck by the visuals. The film is beautiful. Water and hair have always been the most difficult elements for 3-D animators; it’s the reason plastic toys were a good place for Pixar to start. Tangled and Brave gave Disney a chance to master the elements of hair and Moana proved to be its final conquest of water. Disney went so far as to cast the ocean as its own character. That’s just Disney showing off.

But Moana is hailed a success because of the power of its storytelling. What’s Moana about? Well, most parents would probably tell you its a classic adventure story that gives the cliche and outdated princess characterization of a damsel in distress the modern refresh it has long needed. Moana is courageous, determined, and headstrong. She manages to save her family, restore the balance of nature, and council a Demigod out of his self-loathing and back into his own heroic tale. Moana is drawn into this epic role by the call of the ocean—the call to adventure. That call is intoxicating for young and old, maybe more so for the millennial parents stuck in nine-to-five cubicles and sprawling suburban subdivisions. You might say the moral of Moana is simply, follow your inner passion and become who you were truly meant to be.

That’s not a new theme for Disney. They have been refining that story for years. This inner search for a true identity stretches all the way back to a cricket and his famous advice, “when you wish upon a star, makes no difference who you are. Anything your heart desires will come to you.” But even that isn’t ultimately Disney’s innovation. Disney’s model for the modern adventure and hero can trace its roots back to men like Joseph Campbell.

Campbell was a mythologist, a 1940s Indiana Jones-type who traveled to exotic places in those silver piston prop planes out of Casablanca. Campbell explored some of the most remote people groups of the world and collected their myths—stories about creation and struggle, the volatile temperaments of their gods, and, on occasion, the heroes who triumphed over it all. After years of collecting these stories, Campbell developed what he coined “the monomyth”: the single plot encompassing all great legends across every religion and tribe.

Campbell explained:

“The usual hero adventure begins with someone from whom something has been taken, or who feels there is something lacking in the normal experience available or permitted to the members of society. The person then takes off on a series of adventures beyond the ordinary, either to recover what has been lost or to discover some life-giving elixir.”

Eventually, Campbell would come to crystallize his story framework into the now universal advice, “follow your bliss.”

Campbell’s universal plot for a hero’s journey is quickly becoming our culture’s expectations for finding each of our identities. Disney writers and animators often knowledge the work of Campbell as inspiration for their own storytelling. Campbell’s hero arc has shaped movies like The Lion King, The Matrix, The Hunger Games, and Star Wars. George Lucas was religious in his devotion to Campbell’s work.

I realize I’m now at the laborious point where you, as the reader, are getting tired. You expected a puff piece on some heartfelt life lesson from Moana, and instead, you are being dragged into the under-arching narrative supper-structure of Disney storytelling with its implications for developing culture, all of this like some banal college lecture on literary plot diagraming. But I think it’s worth being aware of what you’re watching.

The stories our culture is telling serve as the scaffolding for a modern society and an ideal human identity. Every movie your child watches speaks a word about who they are and how they should identify with the world around them. And Disney, along with our broader culture, has been slowly shifting the portrayal of a hero to shape the cultural shift in our values.

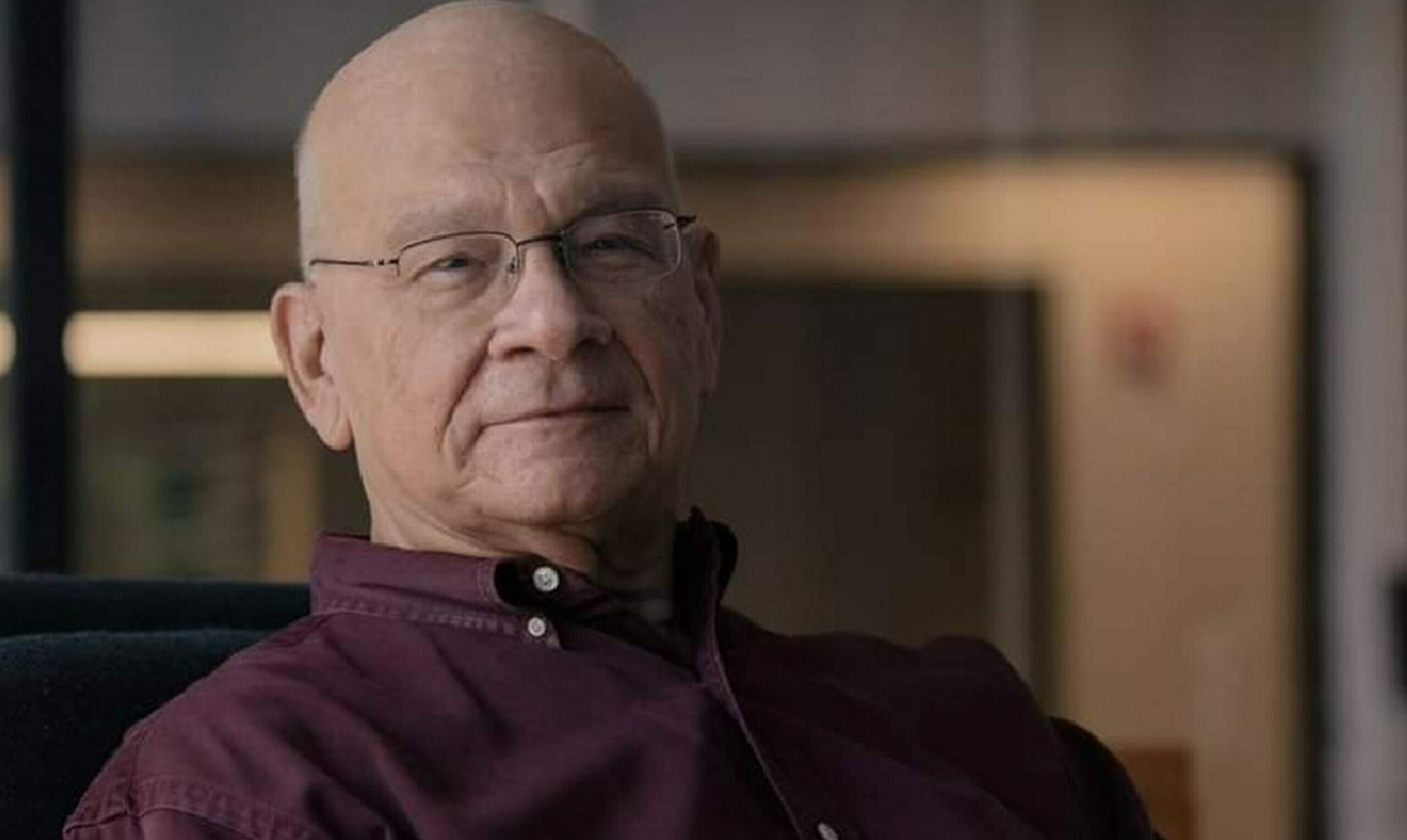

Tim Keller has done important work in diagnosing this modern adaptation of the hero identity. He writes:

“Our cultures are highly individualistic. There is no duty higher than plumbing the depths of your own desires to find out who you want to be. In modern narratives, the protagonist is usually a person who bravely casts off convention, breaks the rules, defies tradition and authority to discover him or herself and carve out a new place in the world. In ancient tales, the hero was the person who did just the opposite, who put aside inner dreams, aspirations, doubts, and feelings to bravely and loyally fulfill their vows and obligations.” (Think of It’s a Wonderful Life as a more modern example.)

The modern adventure story has become the tale of discovering who you want to be and embracing it with single-mindedness, no matter the cost. And while that may seem positive it makes the message of a messiah who would give his life and call us to sacrifice our own foolishness, maybe even incomprehensible.

Let me show you what the story of Moana really does.

A Girl, A Crab, And A Demigod

At the center of the Moana story is the question of identity.

Moana is born on an island. She is born a princess, daughter of the chieftain. She is born into certain expectations and responsibilities concerning her future. Much of her identity has been inherited. But her heart’s desires are incongruent with those expectations of her. Her heart pulls her out onto the open ocean. The movie opens with her family’s struggle to help her integrate who she is with the presumptions of her people—her commitments. But she battles the longing of her own “bliss.”

It’s fascinating because this debate—community expectations and self-expression—are presented in one of the movies catchiest songs, “Where you are”—what my kids call “The Island Song.”

Moana, it’s time you knew

The village of Motunui is

All you need

…

Don’t walk away

Moana, stay on the ground now

Our people will need a chief

And there you areThere comes a day

When you’re gonna look around

And realize happiness is

Where you are

“Happiness is where you are,” sounds like a perfectly legitimate moral for a children’s movie. But, remember, this is the setting that’s holding Moana back. It’s the expectations of the island and her family that lock Moana into a suffocating and claustrophobic version of her self. The songs are catchy, but for Moana, the expectations are crushing.

Take the movies next song. In response to her families expectations of commitment, Moana sings:

I wish I could be the perfect daughter

But I come back to the water, no matter how hard I try

…

I know everybody on this island, seems so happy on this island

Everything is by design

I know everybody on this island has a role on this island

So maybe I can roll with mineI can lead with pride, I can make us strong

I’ll be satisfied if I play along

But the voice inside sings a different song

What is wrong with me?

That question—“the voice inside sings a different song”—is the conflict of the entire movie and one which resonates with a generation of parents listening from the front seats of their Honda Odysseys. Will Moana give in to the limiting expectations of others or will she bravely shed off the expectations of her community to embrace who she is as an individual.

Always pay attention to the music; the music is the driving force of Disney movies. Where Disney can say most bluntly what the story is about. Moana’s song comes at about the same point in the story that Frozen gave us “Let it go.” Maybe you remember these lines:

The wind is howling like this swirling storm inside

Couldn’t keep it in, heaven knows I’ve tried

Don’t let them in, don’t let them see

Be the good girl you always have to be

Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know

Well, now they know

Let it go, let it go

Frozen sounds a lot like Moana. It is the new hero story. The struggle and test of courage to embrace who you really are, to shed the expectations of others. And so, Moana, called by the ocean with an epic responsibility to restore order, sets sail. From this point in the story, Moana’s pursuit of her own self-understanding follows a plot rising and falling with alternative possibilities for her identity:

Option One: Please People — Maui

Maui is a buff, tattooed demigod who continually rejects and mocks Moana because of her size, age, gender, and lack of way-finding skills. He can’t see the heroin inside. He mocks the ocean that calls her; he mocks the sense of destiny Moana lives by. “The ocean is straight up kooky-dooks!” The call to adventure, the call of self-discovery Moana feels it crazy. But before too long, Moana uncovers Maui’s own broken attempts to reconcile his identity.

Maui had spent his life attempting to please humans, hoping that their love and affection would help him heal the deep wounds of previous rejection. Maui too has been looking for an identity. He has been hoping to find it in the acceptance of those he serves. He has lost himself in an attempt to please others. An expression of the thing Moana has fled.

The giant crab, Tamatoa (who we will get to in just a moment) puts it pretty succinctly for Maui:

Now it’s time for me to take apart

Your aching heart

Far from the ones who abandoned you

Chasing the love of these humans

Who made you feel wanted

You tried to be tough

But your armor’s just not hard enough

Option Two: Accumulating Possession — Tamatoa

Tamatoa represents another character caught in an identity-driven crisis. His song critiquing Maui’s love for human approval offers his own alternative: possessions. Tamatoa is a giant monster crab with a cave full of remarkable treasures. In fact, Tamatoa has covered his body with a skin of gold and jewels. In case the image isn’t obvious enough, Tamatoa explains to Moana his take on identity:

Did your granny say listen to your heart,

“Be who you are on the inside”

I need three words to tear her argument apart

Your granny lied!

I’d rather be

Shiny

Like a treasure from a sunken pirate wreck

Scrub the deck and make it look

Shiny

I will sparkle like a wealthy woman’s neck

That’s pretty explicit. Tamatoa secures his identity through his accumulation of possessions. I think Disney is taking a pretty obvious shot at Baby-boomers and their accumulation of wealth—like a diamond on a wealthy woman’s neck? Nothing is more unsightly to a young millennial audience than the ostentatious displays of wealth that defined a previous generation. Rejecting adventure for a home full of money is everything millennials abhor.

Option Three: Anger and Violence — Ta Ka

With Ta Ka, Disney makes its biggest philosophical/theological point. There is also an identity crisis at the heart of the film’s quasi-villain, Ta Ka, a fire hurling lava monster who ferociously guards the ruined island of Te Fiti. Ta Ka is the obstacle to Moana’s goal, restoring the heart of Te Fiti. (By now you should be picking up on the symbolism of returning a heart to the island as a symbol of Moana learning to find and embrace her own heart).

When Moana finally reaches the island of Te Fiti, there is no island left to restore. Te Fiti is gone. But Moana realizes what everyone has been missing. The fire spewing Ta Ka is the island mother god, Te Fiti. Ta Ka is Te Fiti without a heart. With its heart removed, the creator God becomes the embodiment of violence, destruction, isolation, and rage. Te Fiti’s identity had been stolen. Without a sense of who she really was, she had transformed from a nurturer to a destroyer. From a God to a monster.

What Moana recognizes is that the villain is no villain, just a misunderstood goddess of life who, having lost her identity, now wreaked havoc. There are no villains, only individuals who have lost their own way. This is a massive point for Disney. There are no “bad guys,” only individuals who have been robbed of their individuality. Everyone has the potential to be a hero. What holds us back is a lack of faith in ourselves.

Moana suddenly finds a kind of kindred spirit with Ta Ka, protagonist and antagonist recognizing the same inner struggle. It’s one of the most moving moments of the film as Moana sings a song fittingly titled, “Know Who You Are.”

I have crossed the horizon to find you

I know your name

They have stolen the heart from inside you

But this does not define you

This is not who you are

You know who you are

It’s worth noting that Moana doesn’t tell Ta Ka who she is. She turn’s Ta Ka’s attention inward. “You know who you are.” True identity is continually pitched as an inward self-attention.

The song is sung for Ta Ka, but it is also Moana’s song. Moana’s recognition of Te Fiti is simultaneously the realization of her own identity and heroism and the cure for the darkness that is spreading from island to island. This is the real darkness, not evil but crushing expectations and lost identity.

Evil is a misidentification, a person trapped by characterization—a heart having been stolen. Hope comes by placing the heart back at the center—a person restored. Knowing who you are is the restorative salvation that puts the world back into harmony. Finding your heart and embracing it brings forth life out of darkness.

Moana is a story about embracing your true identity by embracing your heart’s deepest desires, even if it means sacrificing the expectations of those around you. Moana is a story about salvation through self-discovery.

Every Man A Hero & The Foolishness of the Cross

Disney stories tend to reflect culture. And there is no mistaking Moana as anything other than a tale of our time. Moana is a part of a much larger shifting cultural narrative that goes something like: Deep inside your heart is who you really are, but too often the traditional authorities of society—family, cultural values, and religion—are holding you back. The real adventure of life is having the courage to be yourself, to discover yourself. Judgment becomes the worst of sins and confident expressions of individuality our salvation.

A generation of kids—my kids—are being raised to believe that anything other than radical devotion to their inner desires is a capitulation. The only hope of happiness is in the pursuit of your heart’s desires. Undiscerning parents continue planting the seeds that undermine their own authority, relationships, and influence. We echo the cultural cliches because we believe them. We want the same adventure. Is it any surprise that after three decades of urging youth to “follow their bliss,” we have developed a generation awash in discontentment and shallow commitments. From restless careerism to prolonged adolescence, finding the bliss of your heart’s desires is proving far more difficult than Moana’s quest across the ocean.

It sounds so simple, follow your passions. But most days I can’t decide what to order at the drive-thru window. And I’m supposed to figure out who I want to be fifty years from now.

There is no denying good things in the story of Moana. A female heroine, her return home to her family, the risk of her own safety to restore the ecology of her island. It’s not hard to tease out more palatable morals, but the real question isn’t what good can we find. The real question is what does my son and daughter take away for themselves. The most obvious moral of Moana is that individuality is the great adventure. That is a massive shift in what it means to be a hero. And it is a shift that makes the call of Christ more and more peculiar and difficult to embrace.

From this desperate and insecure need for a self-achieved identity, we expect our children to produce values like courage, sacrifice, conviction, commitment, and respect. C.S. Lewis captures the predicament well:

“We continue to clamour for those very qualities we are rendering impossible. You can hardly open a periodical without coming across the statement that what our civilization needs is more ‘drive’, or dynamism, or self-sacrifice, or ‘creativity’. In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

It’s not hard to ride the emotional wave of Moana’s self-achieved salvation all the way home from the theater. But once we arrive back home into the challenges of our pedestrian lives, it’s difficult to sustain the idea that we are each a hero—that each of us is on our own great adventure. Eventual the optimism of the opportunity turns into a crushing weight of self-expectation. Why can’t we figure it out? Why can’t we chart our own course to happily ever afters? Why are we plagued down by failure, broken relationships, and insecurity?

In a world desperately exploring-self desire and self-achievement, there is very little room for the message of the cross. Sure, the Christian gospel can be neatly replotted onto Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. You can pitch Christianity as a path to self-discovery. You can offer the gospel as a means to individuality and structure churches to play the part of guide for each religious adventurer. Most towns offer a buffet of religious options, perfect for the person seeking to construct just the right system for achieving their best life.

We may preach commitment and death-to-self, but we scramble to find the right branding, stage design, and lobby coffee to earn positive social reviews. Christ becomes our cheerleader and spiritual gift assessment the tools for self-discovery. We get obsessed with talking about calling but lose interest in the common callings of husband, father, and member. We find ways to fit the gospel into the new hero expectations of our culture. Christ calls us into our own adventure promising our own heroic self-discovery.

Plus who wants to suggest to Moana, “For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for My sake will find it.” The adventure of the open seas sounds so much more appealing than self-denial and self-death. Who wants meekness and poverty when you can have adventure and achievement.

So, should you boycott Moana? I don’t think so. My kids watch it, but we also talk about it. We talk about its message. We talk about how it applies to life. We talk about how our faith helps us see things Moana doesn’t. We compare Moana’s story to Jesus’. We reconcile that often, especially in Jesus’ story, we aren’t the main character.

The point is not to boycott, but engage. Engagement means parents are going to have to think a lot more deeply about the stories the world is offering their children and how our Christian stories differ. It means we need to better understand our own hearts and desires. It means we need to question many of the cliches we speak about life and meaning. It means we need to take a long look at what our lives have reaped from self-pursuit.

Moana’s grandmother had been the first to offer Moana the potential salvation of self-discovery. She put it perfectly, “Once you know what you like, well, there you are.” It sounds so right, but it cuts deeply against the call of Christ, “Whoever loses their life for me will save it.”